My Twitter feed just exploded. Yet another study has been released claiming that if we all just gave up beef, the planet would be saved, Elvis would come back from the dead, and rainbow-belching unicorns would graze the Northern Great Plains. I may have exaggerated a little with the latter two claims, but the extent of media coverage related to the paper “Land, irrigation water, greenhouse gas and reactive nitrogen burdens of meat, eggs and dairy production in the United States” seems to suggest that the results within are as exciting as seeing Elvis riding one of those unicorns…but they’re also about as believable.

My Twitter feed just exploded. Yet another study has been released claiming that if we all just gave up beef, the planet would be saved, Elvis would come back from the dead, and rainbow-belching unicorns would graze the Northern Great Plains. I may have exaggerated a little with the latter two claims, but the extent of media coverage related to the paper “Land, irrigation water, greenhouse gas and reactive nitrogen burdens of meat, eggs and dairy production in the United States” seems to suggest that the results within are as exciting as seeing Elvis riding one of those unicorns…but they’re also about as believable.

Much as we’d all like to stick our fingers in our ears and sing “La la la la” whenever anybody mentions greenhouse gases or water footprints, we cannot deny that beef has an environmental impact. Yet, here’s the rub – so does every single thing we eat. From apples to zucchini; Twinkies to organically-grown, hand-harvested, polished-by-mountain-virgins, heirloom tomatoes. Some impacts are positive (providing habitat for wildlife and birds), some are negative (nutrient run-off into water courses), but all foods use natural resources (land, water, fossil fuels) and are associated with greenhouse gas emissions.

So is this simply another attack on the beef industry from vegetarian authors out to promote an agenda? Possibly. The inclusion of multiple phrases suggesting that we should replace beef with other protein sources seems to indicate so. But regardless of whether it’s part of the big bad vegan agenda, or simply a paper from a scientist whose dietary choices happen to complement the topic of his scientific papers, the fact remains that it’s been published in a world-renowned journal and should therefore be seen as an example of good science.

Or should it?

I’m the first to rely on scientific, peer-reviewed papers as being the holy grail for facts and figures, but there’s a distressing trend for authors to excuse poor scientific analysis by stating that high-quality data was not available. It’s simple. Just like a recipe – if you put junk in, you get junk out. So if one of the major data inputs to your analysis (in this case, feed efficiency data) is less than reliable, the accuracy of your conclusions is….? Yep. As useful as a chocolate teapot.

Feed efficiency is the cut-and-paste, go-to argument for activist groups opposed to animal agriculture. Claims that beef uses 10, 20 or even 30 lbs of corn per lb of beef are commonly used (as in this paper) as justification for abolishing beef production. However, in this case, the argument falls flat, because, rather than using modern feed efficiency data, the authors employed USDA data, which has not been updated for 30 years. That’s rather like assuming a computer from the early 1980’s (I used to play “donkey” on such a black/green screened behemoth) is as efficient as a modern laptop, or that the original brick-sized “car phones” were equal to modern iPhones. If we look back at the environmental impact of the beef industry 30 years ago, we see that modern beef production uses 30% fewer animals, 19% less feed, 12% less water, 33% less land and has a 16% lower carbon footprint. Given the archaic data used, is it really surprising that this latest paper overestimates beef’s environmental impact?

The authors also seem to assume that feed comes in a big sack labeled “Animal Feed” (from the Roadrunner cartoon ACME Feed Co?) and is fed interchangeably to pigs, poultry and cattle. As I’ve blogged about before, we can’t simply examine feed efficiency as a basis for whether we should choose the steak or the chicken breast for dinner, we also have to examine the potential competition between animal feed and human food. When we look at the proportion of ingredients in livestock diets that are human-edible (e.g. corn, soy) vs. inedible (e.g. grass, other forages, by-products), milk and beef are better choices than pork and poultry due to the heavy reliance of monogastric animals on concentrate feeds. By-product feeds are also completely excluded from the analysis, which makes me wonder precisely what the authors think happens to the millions of tons of cottonseed meal, citrus pulp, distillers grains, sunflower seed meal etc, produced in the USA each year.

Finally, the authors claim that cattle use 28x more land than pigs or poultry – although they acknowledge that cattle are raised on pasture, it’s not included in the calculations, which assume that cattle are fed feedlot diets for the majority of their life. This is a gross error and underlines their complete ignorance of the U.S. beef industry. Without cow-calf operations, the U.S. beef industry simply would not exist – efficient use of rangeland upon which we cannot grow human food crops both provides the foundation for the beef industry and creates and maintains habitats for many rare and endangered species of plants, insects, birds and animals.

Want to know how to reduce the environmental impact of food production overnight? It’s very simple – and it doesn’t involve giving up beef. Globally we waste 30% of food – and in developed countries that’s almost always avoidable at the consumer level. Buy the right amount, don’t leave it in the fridge to go moldy, and learn to use odd bits of food in soups or stews. Our parents and grandparents did it out of necessity – we can do it to reduce resource use and greenhouse gas emissions; and take the wind out of the sails of bean-eating anti-beef activists.

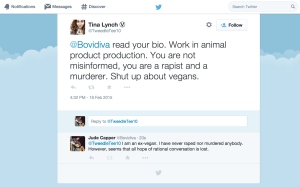

When the report was released, my Twitter notifications, Facebook feed and email inbox exploded. Memes like the one to the left appeared on every (virtual) street corner, and the report was mentioned in every online newsletter, whether agricultural or mainstream media. It’s this press coverage rather than the content of the report, that really concerns me.

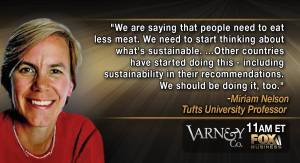

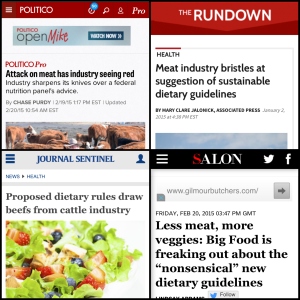

When the report was released, my Twitter notifications, Facebook feed and email inbox exploded. Memes like the one to the left appeared on every (virtual) street corner, and the report was mentioned in every online newsletter, whether agricultural or mainstream media. It’s this press coverage rather than the content of the report, that really concerns me. Yet people do pay attention to headlines like “Less meat, more veggies: big food is freaking out about the “nonsensical” new dietary guidelines” and others shown to the left. The media sub-text is that big bad food producers (so different from the lovely local farmer who sells heirloom breed poultry at $18/lb at the farmers market) are appalled by the release of this governmental bad science that’s keeping them from their quest to keep you unhealthily addicted to triple cheeseburgers washed down with a 500-calorie soda, and will do anything to suppress it.

Yet people do pay attention to headlines like “Less meat, more veggies: big food is freaking out about the “nonsensical” new dietary guidelines” and others shown to the left. The media sub-text is that big bad food producers (so different from the lovely local farmer who sells heirloom breed poultry at $18/lb at the farmers market) are appalled by the release of this governmental bad science that’s keeping them from their quest to keep you unhealthily addicted to triple cheeseburgers washed down with a 500-calorie soda, and will do anything to suppress it.