Further to yesterday’s blog post here, I was asked for my views on this article in the Telegraph by companion animal vet Pete Wedderburn. Given my propensity to use 17 words when three will do (I blame PhD training…) it was easier to blog about it than reply via Twitter.

To be fair to Dr Wedderburn, his article does note the importance of economies of scale and potential for targeted veterinary care on large operations; and it’s absolutely true that we, as consumers, demand affordable food. The average Briton spends only 8.2% of their income on food. Given how much we should value the nutritional advantages provided by meat, milk and eggs for growth, development and health, I have no issue with the suggestion that we should pay more (if needed) for higher welfare animal products.

To be fair to Dr Wedderburn, his article does note the importance of economies of scale and potential for targeted veterinary care on large operations; and it’s absolutely true that we, as consumers, demand affordable food. The average Briton spends only 8.2% of their income on food. Given how much we should value the nutritional advantages provided by meat, milk and eggs for growth, development and health, I have no issue with the suggestion that we should pay more (if needed) for higher welfare animal products.

Yet that’s where the argument gets difficult, and in the case of the Telegraph article, moves away from logic, science and economics towards anthropomorphism, emotion and the supposition that we can assess animal welfare based on human experience. If there was an emotive language quotient for the article, it went up significantly in the anti-mega-farm section.

Unpalatable (pun intended) a truth as it may be, we do not apply to the same standards to animals that we intend to eat (cows, pig, chickens) as to companion animals (it’s somewhat amusing that the Telegraph article was published within the “Pets” section), or indeed to animals that we consider to be pests (rats, mice, insects etc). Do many of us worry about the living conditions of house spiders or wasps, aside how we can kill them when they become a menace? No. Activist groups claim that this is speciesism, but I’d contend that it’s simply a factor of being human. We cannot have our bacon and eat it – if we apply the same standards to pets and farm animals (eliminating the “double standard” cited in the article) then perhaps by extension, just as we wouldn’t tuck into a steak from our pet labrador, we should cease to eat farm animals.

The ultimate irony is that, if asked, none of us would be happy to be killed and eaten. Slaughter is an inevitable truth of meat production, regardless of the conditions in which the animal is reared – if we cannot reconcile ourselves to the fact that we, as humans, would not be happy with that outcome, can we really assume that we can speak for animals’ preferences in any other circumstance?

“Animal welfare is a significant one [issue]: intensively kept farm animals never experience the open air, and never see blue skies” Being outside in the sunshine is undeniably lovely. However, we’re in the midst of the ill-named British “summer”. The rain is driving down and the Hereford cattle in the field I drove past five minutes ago were sheltering under a tree, ironically, voluntarily choosing to be in far closer quarters than cattle housed in a shed. We need to move away from the pervasive but false image of perpetual blue skies and sunshine. Would I personally wish to exist within the human equivalent of a battery cage? Of course not. Yet neither would I wish to be outside in pouring rain and cold wind. It’s all about balance. Do I know what a cow, chicken or pig prefers? No. We need further research to elucidate animal preferences and, *if* required, to amend our farming systems.

“Animal health is another concern: with thousands of animals living so closely together, the risk of rapid spread of contagious disease must be higher.” At face value – true. However, as with so many rhetorical statements, this bears further examination. The risk is higher. Not the incidence, nor the mortality or impact on the animals, the risk. We can have a significant increase in risk that still makes little difference to the likelihood of an event happening. Take, for example, the announcement that processed meat increases the risk of colon cancer by 18%. Immediate media reaction? “Bacon will totally kill you!” Actual change in relative risk for the average person? An increase from 5 people out of every 100 contracting colon cancer, to 6 people out of every 100. Using blanket statements about increased risk, without backing them with any science or relative risk metrics (i.e. the likelihood of an incident actually occurring) is meaningless, yet an effective fear-mongering tool. If any farm (regardless of size) has excellent health plans in place, employs effective veterinary supervision and treatment and has appropriate biosecurity and isolation for sick animals, there is no reason to suggest that disease X will spread unchecked. Why did the UK government mandate for poultry to be housed when the risk of avian influenza was high? Because it’s spread by contact with wild birds and poultry, in precisely the supposedly healthy conditions proposed by the Telegraph article.

The supposition that “…if something does go wrong, it can go wrong on a massive scale, affecting thousands of animals at one time” is again correct – with one significant caveat. Relative risk again comes into play – why would a ventilation system be more likely to fail on a large operation than a small operation? A risk may exist, but again, it’s the relative risk (ignored by the Telegraph article) that is more important. To use a human example, if the power supply fails to a large hospital, we would assume that they would have more back-up systems in place than in a small cottage hospital. Why should Dr Wedderburn assume that large farms do not have operating procedures and practices in place to deal with disaster situations? In the USA last year, 35,000 cattle died during a two-day snowstorm, the majority not housed, but in open fields. Being able to control the environment and feed supply is a major advantage of housed systems – assuming the worst case scenario is business as usual is misleading at best.

Animal welfare is a useful tool with which to bash specific farming operations, because it carries a certain intangibility. What does good animal welfare really mean? How is it assessed? Are healthy animals automatically “happy” or in a good welfare state? Perhaps it’s time to revisit and challenge the rhetoric. Given that high-producing livestock should, by definition, be healthy, does that mean that we can use milk or meat yield as an indicator of welfare? Not necessarily. If we have to reduce the use of critically-important antibiotics, will animal welfare suffer? Not if we use other husbandry measures to prevent the disease from occurring in the first place (see figure below). Is a cow who is genetically programmed to produce 40 kg of milk per day automatically more stressed than one who is only programmed to produce 20 kg of milk? Few people would suggest that a woman capable of producing copious quantities of breast milk is more stressed than one producing a small amount, yet we try to apply this logic to livestock.

Emotion is a far more effective tool to lead conversations about controversial issues than science – perhaps its time to take the bull by the horns and get in touch with our touchy-feely side to communicate as the activists do. Ultimately we need to reassure consumers that, as with all issues, there’s no ideal or one-size-fits-all farming system, just a million shades (sheds!) of grey.

Emotion is a far more effective tool to lead conversations about controversial issues than science – perhaps its time to take the bull by the horns and get in touch with our touchy-feely side to communicate as the activists do. Ultimately we need to reassure consumers that, as with all issues, there’s no ideal or one-size-fits-all farming system, just a million shades (sheds!) of grey.

Two weeks ago, I sat in the audience for the Semex conference and heard two different presenters talking about the increasing market for plant-based foods and the myths, mistruths and misconceptions that abound about dairy farming. As a scientist, I know that we need five pieces of positive information to negate every piece of negative information. Lo and behold, #Februdairy was born!

Two weeks ago, I sat in the audience for the Semex conference and heard two different presenters talking about the increasing market for plant-based foods and the myths, mistruths and misconceptions that abound about dairy farming. As a scientist, I know that we need five pieces of positive information to negate every piece of negative information. Lo and behold, #Februdairy was born! It’s a simple concept, a campaign to celebrate all things that are wonderful about dairy – from cows to cheese, young farmers to yogurt.

It’s a simple concept, a campaign to celebrate all things that are wonderful about dairy – from cows to cheese, young farmers to yogurt.

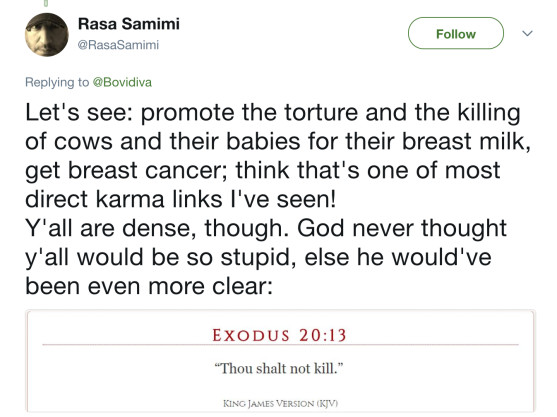

We should not criticise anybody’s choice of food, diet or lifestyle – it’s wonderful that we all are free to make the choices that suit our beliefs and philosophies. If you don’t eat or enjoy dairy – that’s entirely your choice and it’s great that you have alternative foods that certainly weren’t around when I was a vegan 25 years ago!

We should not criticise anybody’s choice of food, diet or lifestyle – it’s wonderful that we all are free to make the choices that suit our beliefs and philosophies. If you don’t eat or enjoy dairy – that’s entirely your choice and it’s great that you have alternative foods that certainly weren’t around when I was a vegan 25 years ago!

For example, is suggesting that we shouldn’t drink milk past-weaning because other animals do not, either upheld by science (

For example, is suggesting that we shouldn’t drink milk past-weaning because other animals do not, either upheld by science (

To be fair to Dr Wedderburn, his article does note the importance of economies of scale and potential for targeted veterinary care on large operations; and it’s absolutely true that we, as consumers, demand affordable food. The average Briton spends

To be fair to Dr Wedderburn, his article does note the importance of economies of scale and potential for targeted veterinary care on large operations; and it’s absolutely true that we, as consumers, demand affordable food. The average Briton spends  Emotion is a far more effective tool to lead

Emotion is a far more effective tool to lead  The Advertising Standards Authority in the UK have just ruled that it’s

The Advertising Standards Authority in the UK have just ruled that it’s

Today is Cow Appreciation Day and

Today is Cow Appreciation Day and

Last week I was lucky enough to chat with the fabulous

Last week I was lucky enough to chat with the fabulous