I spoke at the International Livestock Congress back in January 2012, and at the end of the day, had the pleasure of listening to a couple of distinguished industry colleagues wrapping up the day’s talks in Q&A format. The conversation went thus (with names changed to spare the blushes of the individuals concerned):

I spoke at the International Livestock Congress back in January 2012, and at the end of the day, had the pleasure of listening to a couple of distinguished industry colleagues wrapping up the day’s talks in Q&A format. The conversation went thus (with names changed to spare the blushes of the individuals concerned):

Dr. R: “Jude Capper talked about the importance of having credible industry spokespeople to communicate with consumers – how do you suggest that we improve the image of beef sustainability?”

Dr. S: (hitches up his pants, stands up straight): “Well, Jude Capper is credible because she is female…” (pause while the shoulders and eyebrows of 50 or so female graduate students in the audience almost hit the ceiling) “…and she’ll be even more credible when she has children.”

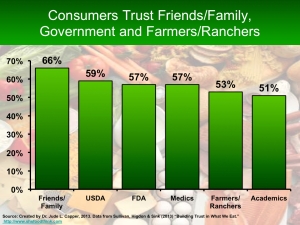

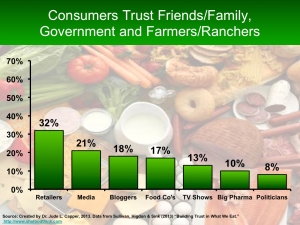

If any one of those graduate students had a gun, a knife or even a sharpened pencil, I think it’s a safe bet that Dr. S would not still be on this earth – the air was so thick with “How dare that chauvinistic old man SAY that?!” it was like spending a weekend in a cigar bar. Yet Dr. S was absolutely right (although he’d probably have fewer voodoo dolls created in his image if he’d explained his statement) – female scientists, especially those who have children, are trusted by female consumers more than the traditional scientific image of an older man in a white lab coat. Why? Well it’s all about how we relate to others. We’re more likely to trust people who seem more like ourselves (age, ethnic group, profession, socioeconomic class) than those with whom we perceive we have little in common. It’s therefore not surprising that recent research (graphs below) shows that we trust our friends and families more than we trust the media, TV shows (take that, Oprah!) or politicians.

I’m excited to announce that I’m gaining credibility by the day…pound by pound…literally. At almost 7 months pregnant, the most popular question I have at conferences is still “How do I communicate this information to the consumer?”, but it’s swiftly followed by “When is your baby due?”. My baby bump has given me more opportunities for conversations about the importance of beef in pregnancy nutrition with people in airports, on planes and in the grocery store in the past few months than in the rest of my life to date – and I haven’t been the person starting the conversation.

I’m excited to announce that I’m gaining credibility by the day…pound by pound…literally. At almost 7 months pregnant, the most popular question I have at conferences is still “How do I communicate this information to the consumer?”, but it’s swiftly followed by “When is your baby due?”. My baby bump has given me more opportunities for conversations about the importance of beef in pregnancy nutrition with people in airports, on planes and in the grocery store in the past few months than in the rest of my life to date – and I haven’t been the person starting the conversation.

So what does this mean for communicating with the consumer? Even in these enlightened times, women still make the bulk of food-buying decisions, so we need to specifically target the female consumer . In almost every talk I do, I urge farmers and ranchers to put photos, videos and status updates on Facebook and Twitter so that they can reach their crazy cousin, unsure uncle or doubting daughter, living in a far-off city, with positive messages about agriculture. This time, I’m widening the net – if you happen to be male*, please also ask your wife, girlfriend, daughter, mother, granddaughter or niece to post and let the female consumer know why we do what we do every day, why beef is a great choice for our families, and why we spend time for caring for baby calves almost as if they are our own children. If you’re female… well, have at it! There are already some excellent blogs out there from women in the livestock industry (e.g. DairyCarrie, The South Dakota Cowgirl, Feedyard Foodie, Mom at the Meat Counter, The Real Farm Wives of America and The Pinke Post) – let’s push back against all the tide of anti-meat or anti-conventional agriculture misinformation with more real-life experiences from the parents of the next generation of farmers, ranchers and consumers.

*Note that I am NOT suggesting that only women should blog or post on social media! This is simply about making that female-female connection that, whether we like it or not, does promote an instant degree of trust