The recent report by the advisory committee to the USDA dietary guidelines has certainly caused a media stir in the past week or so. There’s a lot of nutritional common sense in the report – eat more fruit, veg, and dairy, reduce carbs and sweetened drinks/snacks, and moderate alcohol intake. Yet there’s a kicker – from both a health and a sustainability perspective, Americans should apparently be guided to consume less animal-based foods.

When the report was released, my Twitter notifications, Facebook feed and email inbox exploded. Memes like the one to the left appeared on every (virtual) street corner, and the report was mentioned in every online newsletter, whether agricultural or mainstream media. It’s this press coverage rather than the content of the report, that really concerns me.

Individuals don’t pay a lot of attention to a government report on nutrition. Despite the fact that six updates to the guidelines have been released since their inception in 1980, we are all still eating too many Twinkies in front of the TV and super-sized takeout meals in the car, rather than chowing down on broccoli and lentil quinoa bake.

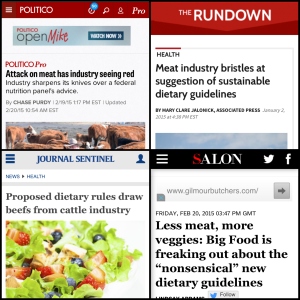

Yet people do pay attention to headlines like “

Less meat, more veggies: big food is freaking out about the “nonsensical” new dietary guidelines” and others shown to the left. The media sub-text is that big bad food producers (so different from the lovely local farmer who sells heirloom breed poultry at $18/lb at the farmers market) are appalled by the release of this governmental bad science that’s keeping them from their quest to keep you unhealthily addicted to triple cheeseburgers washed down with a 500-calorie soda, and will do anything to suppress it.

This makes me wonder – at what point do we need quiet, stealthy change, rather than loud protests that attract the attention of people who would otherwise never have read about the guidelines? At what point does industry protesting seem like a modern version of “The lady doth protest too much“?

Rather than posting on Facebook or Twitter that the report is nonsense because the committee of nutritionists ventured into the bottomless pit that is sustainability; why don’t we instead extol the virtues of producing high-quality, nutritious, safe and affordable lean meat, and aim to reach the people who haven’t seen the hyperbolic headlines or read the guidelines simply because they’ve seen a lot of talk about them on Twitter? The old showbiz saying that there’s no such thing as bad publicity certainly applies here – the extent of the reporting on the industry backlash against the report means they have probably been noted by far more people that they otherwise might.

The impact of the dietary guidelines recommendations upon purchasing programs is far higher than on individuals, and does give rise to concern. Globally, one in seven children don’t have enough food, and school lunches are often the only guaranteed source of high-quality protein available to children in impoverished families. I may be being overly sceptical, but I suspect that if meat consumption in schools is reduced, it’s unlikely to be replaced with a visually and gastronomically-appealing, nutritionally-complete vegetarian alternative.

Sustainability doesn’t just mean carbon, indeed, environmentally it extends far further than the land, water and energy use assessed by the dietary guidelines advisory committee into far bigger questions. These include the fact that we cannot grow

human food crops on all types of land;

water quality vs. quantity; the need to protect wildlife biodiversity in marginal and rangeland environments; the use of animal manures vs. inorganic fertilisers; environmental costs of sourcing replacements for animal by-products in manufacturing and other industries; and many other issues. Simply stating that meat-based diet X has a higher carbon footprint or land use than plant-based diet Y is not sufficient justification for 316 million people to reduce their consumption of a specific food. Indeed, despite the conclusions of the committee, data from the US EPA attributing only

2.1% of the national carbon footprint to meat production suggests that even if everybody reduced their intake of beef, lamb and pork, it would have a

negligible effect on carbon emissions.

Could we all reduce our individual environmental impact? Absolutely. Yet as stated with regards to dietary change in the advisory report, it has to be done with consideration for our individual biological, medical and cultural requirements. As humans, we have biological and medical requirements for dietary protein, and some would even argue that grilling a 16-oz ribeye is a cultural event. I have every sympathy for the USDA committee*, who were faced with a Herculean task to fulfill, but in this case, they only succeeded in cutting off one head from the multi-craniumed Hydra – and it grew another 50 in its place.

*Many people have already commented on the suitability (or not) of the committee to evaluate diet sustainability, but to give them their due, they do appear to have looked beyond greenhouse gases to land, water and energy use. They are nutrition specialists, not sustainability experts, but it would be difficult (impossible) to find a committee comprising people who were all experts in nutrition, sustainability, economics, policy, behaviour and all the other facets of the report. Nonetheless, the sustainability recommendations appear to be based on a small number of papers, many of which are based on dietary information from other regions (Germany, UK, Italy) which will also have different levels of animal and crop production. As somebody who was born and bred in the UK before moving to the USA I find it difficult to believe that the average American’s diet uses substantially more land (for example) than the average UK person, as cited in the report.

Shameless self-promotion, but very excited to have an essay published in The Wall St Journal today defending conventional beef production.

Shameless self-promotion, but very excited to have an essay published in The Wall St Journal today defending conventional beef production.